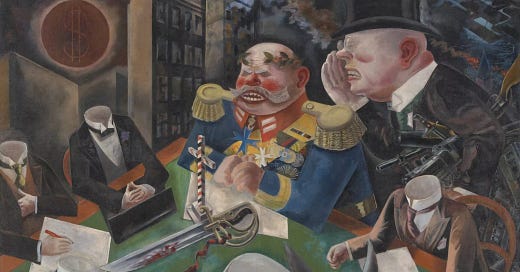

‘The psychology of the whipped dog’

Lessons from Trotsky on the class composition and political conditions of fascism in the 20th century

By Chris Beausang

‘The whole world has collapsed inside the heads of the petty bourgeoisie, which has completely lost its equilibrium. This class is screaming so clamorously out of despair, fear and bitterness that it is itself defined and loses the sense of its words and gestures…The lion’s roar in this case hides the psychology of the whipped dog’. — Leon Trotsky

Bourgeois historians, sociologists, and journalists would have us regard fascism as a symptom of a violence, prejudice, and irrationality fundamental to human nature, rather than a product of a specific conjuncture of political and economic forces that arise when the capitalist system undergoes convulsions and presents an existential threat to the current social order. Under such conditions, a significant faction of the capitalist class is willing to support and encourage street violence against the labour movement and oppressed social groups to recapture the long-term viability of bourgeois rule, even at the expense of forfeiting the immediate exercise of political power. Far from being too costly or disruptive, fascism is in fact compatible with the interests of the capitalist class. In Germany, for example, between 1933 and 1938 industrial profits rose from 6.6 billion marks to 15 billion. Fascism is, therefore, the realisation of capital’s tendency to organise the entirety of social life in its interests.

The lower middle-class of shopkeepers, landlords, and peasants were the key factions in fascist politics. Devastated by the Great Depression in 1929, the petty bourgeoisie in Germany faced inflation, bankruptcy, mass unemployment – not to mention the scores of people killed and wounded in the war – and deteriorated into despair and resentment. Rather than becoming proletarians, these conditions made them uniquely susceptible to reactionary propaganda encoded with a nostalgia for an invented pre-industrial society of purity and plenty. Blame for the erosion of this imagined past lay at the feet of Marxists, the labour movement, and Jews.

Acutely aware of developments in Germany and Italy in the 1920s and 30s, Trotsky recognised the dynamic of a failure to fulfil a proletarian revolution, the betrayal of the working class by social democrats and liberals, and the violent emergence of a reactionary layer of the middle-class as key components for the emergence of fascism. For much of the fourteen-year period known as the Weimar Republic, the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) was often one of the largest parties in the German Reichstag, holding or sharing power for four years. It was the party of the German workers and the dominant influence in the trade-union movement. It was also, however, a party of the establishment with a leadership that was hostile to revolutionary politics and regarded socialism as something to be achieved incrementally through parliamentary means, if at all.

The SPD served as the capitalist state’s most reliable moderators of radical sentiment and compliant managers of the existing order. The SPD’s abdication of responsibility and violent reaction to the working class during the German Revolution of 1918-1919 was a significant barrier to unity with the Moscow-aligned German Communist Party (KPD). SPD leader and German chancellor Friedrich Ebert directed the counter-revolutionary paramilitary friekorps to crush the revolution and assassinate its leaders. The SPD, Trotsky writes, “saved the bourgeoisie from the proletarian revolution, [and] fascism came in its turn to liberate the bourgeoisie from the Social Democracy.”

The actions of European social democracy, when faced with revolutionary conjunctures, meant there was no international support for the diplomatically isolated Soviet state and is a major reason why socialism is no longer an historical force.

This pattern of social democratic inertia with regard to fascism was also seen in Italy. During the biennio rosso (1919-1920) workers seized factories and took control of industry through factory councils, nearly accomplishing the dictatorship of the proletariat. The working class parties baulked, however, paving the way for the rise of Benito Mussolini. The actions of European social democracy, when faced with revolutionary conjunctures, meant there was no international support for the diplomatically isolated Soviet state and is a major reason why socialism is no longer an historical force. Fearing that mobilisation of their membership would escalate into more radical demands, social democratic leaders instead placed their hopes in state representatives to restore normality and made constant concessions to the political right.

Regardless of the conciliatory tendencies of their leaders, the military dictatorship or police state envisioned by the Nazis could not have been installed from above given the sophistication and militancy of the German working class. As such, in alliance with the major industrialists, the landed gentry and the officer corps, the Nazis mobilised their supporters into acts of violence, wearing down the proletariat over time with mass terror and street warfare. In Italy, Mussolini organised the petty-bourgeoisie against the proletariat and forged an alliance between his street-fighting Blackshirts and the embattled capitalists, and was welcomed into establishment politics by the monarchy as a violent defender of the state against the communist threat.

Throughout Trotsky’s exile — enforced by Stalin and his allies in the communist party — he followed developments in Germany, excoriating the SPD, the KPD and the Comintern for their strategic failures at each turn. Trotsky proposed the KPD subordinate those aspects of its direct political objectives (the seizure of state power, the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat) which necessitated an oppositional stance to, and independence from, conciliatory factions of the labour movement. Trotsky predicted that if the KPD retained its critical stance in a united front and pressed for slogans which most closely adhered to the demands of the working class, the rank-and-file of the SPD could be won to an internationalist and revolutionary socialist programme. Trotsky derived his model from his experience as a leader of the Russian Revolution and the joint effort that the socialist parties had made in repelling the threatened military dictatorship of Lavr Kornilov who sought to restore military discipline on the front and crush the organised soviets domestically.

In defense of the revolution, the Bolsheviks temporarily ended their programme of opposition to the Provisional Government and its supporting socialist parties to mobilise a critical mass of the workers against Kornilov. Trotsky calculated that the SPD would make the same decision as the moderate Russian socialists; namely, recognise that Kornilov’s dictatorship represented an existential threat not just to the Bolsheviks, but also to themselves. Instead, the SPD spurned alliances with the KPD and supported the deflationary policies of Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, regarding it as the only means of keeping Hitler out. They also expelled members who criticised this policy in October 1931, leading to a split, with a number of left-SPD members, pacifists, and a section of the Communist Party forming the Socialist Workers Party (SAP).

In December 1931, the SPD launched the ‘Iron Front for Resistance Against Fascism’, a mass organisation embracing the old Reichsbanner, the SPD Youth, labour groups, and liberals. The SPD rank-and-file rallied to this initiative, held mass demonstrations, fought the fascists in the streets and even armed themselves. Trotsky hoped this signaled a new revolutionary initiative but the SAP failed to bring over a significant amount of SPD rank-and-file workers and the SPD’s commitment to the Iron Front was in direct proportion to how much it could act as a safety valve to prevent any further defections from the party.

Trotsky regarded these struggles in Germany as key to the international advance of socialism, as a means of breaking the bureaucratic stranglehold in which the Stalinist clique held the USSR, and correctly foresaw that if the Nazis were to enter into power a European-wide conflagration would follow. But up until the Nazis came into power, the day before they were sent to concentration camps, the Social Democrats indicated their willingness to support Hitler’s programme and their willingness to hand the state over to the fascists rather than risk the left taking the initiative.

Chris Beausang is a writer and critic who was born, and continues to live, in Dublin. His fiction and criticism has appeared in Rupture, new sinews, and The Belfield Literary Review. He blogs at aonchiallach.github.io.

An examination should be undertaken of why significant numbers of working class people stayed loyal to the SPD or more tragically joined the NSDAP rather than the KPD or the Trotskyist/Left Opposition formations.